Impressionism embodies the most buoyant celebration of colours and rhythm. The motion that best dictates Impressionism is fleet: this statement is best exemplified by Monet’s Impression, Sunrise (1872), in which the artist captured the transient but consistent movement of the sun rising to the apex and its reflection on the placid water. With spring reaching to its maturation, the fashion one displays should be blatantly heralding the coming of summer. The Book of Hours illustrated by the Limbourg Brothers represents aptly the fashion shift from the tail-end winter to the sprout of spring, or what also come into mind are the more serene, uninhabited landscape paintings by J.M.W. Turner. Impressionism, I suspect, keys to the fashion worn in mid-spring.

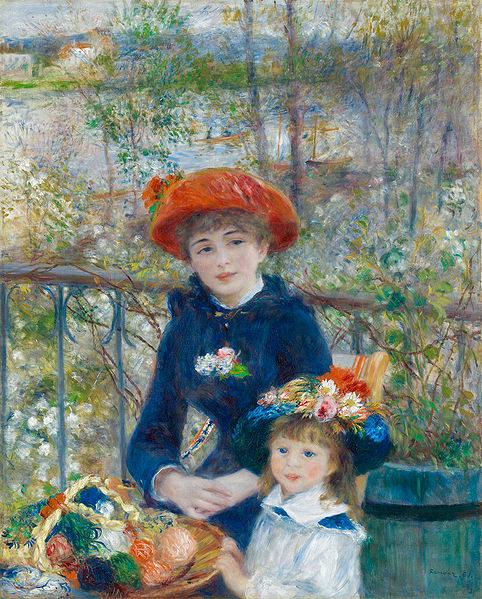

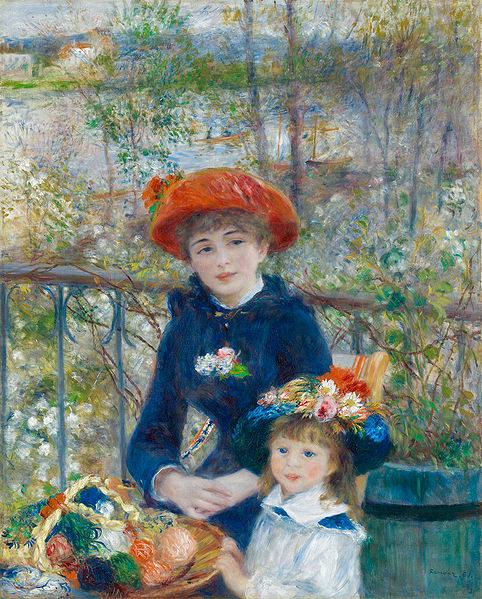

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, On the Terrace (1881)

(from left to right: Betsey Johnson, Anna Sui, Doo-Ri, Spring 2012 via Elle.com)

Renoir stimulated my earliest admiration for art. The artist’s portrayal of wide-eyed ingénue constructed my childhood notion of what an idealized beauty should be. I only realized then as I grew older that such beauty remained illusory. The felicity Renoir’s paintings exudes, however, hardly diminishes even when situating in a world where everything is encouraged to be judged rationally and pragmatically. The exuberance of colours plays a key role in many of Renoir’s famous work. The subtle inflection of tone reminds me of what a typical Romantic music piece will be- the layers of build-up toward a dramatic climax. The climax of Renoir’s painting is its overall presentation, with the pervasive opaqueness created by the Impressionistic loose brushstrokes.

Mary Cassatt, Nurse Reading to a Little Girl (1895)

(from left to right: Carolina Herrera, Lanvin, Oscar de la Renta. Spring 2012 via Elle.com)

With the art world still squeamish to give attention to women artists in the 19th century, Mary Cassatt’s Nurse Reading to a Little Girl (1895) posed as something rather groundbreaking. The painting’s pastel-softness of green and yellow and its sketchy and wilful strokes presaged their prevalence seen in post-Impressionists like Van Gogh and Munch. However, the green and yellow in Cassatt’s painting are a staggering contrast to the unsettling derangement in Van Gogh’s, nor are the strokes indicative of an inferno burning menacingly in most of Munch’s. In Cassatt’s painting, the serenity and harmony will finally prevail.

Camille Pissarro, The Woods at Marly (1871)

(from left to right: L'Wren Scott, Alexander McQueen, Anna Sui. Spring 2012 via Elle.com)

Pissarro’s later work heralds Pointillism, initiated most notably by Seurat and Signac. Being recognized as a landscape painter, it must be a frustration for the work to be classed as something quotidian. Pissarro’s landscape is never quotidian. Amid numerous colourful dots is a passage visibly extending to an unseen end; the depth is thus created. It was an intent for the Pointillists to create an optical illusion by atomizing the painting into dots (at least that was my surmise when I was young, that the artists dissected the painting instead of painstakingly spotting on the colours), such technique does not render the painting into two-dimensional, however, it almost seems like those little dots are endowed with substance.

Edouard Manet, Luncheon on the Grass(1863)

(from left to right: Burberry Prorsum, Paul Smith, Yves Saint Laurent. Spring 2012 via Elle.com)

Manet’s nudes are my favourite, despite their bodies were once criticized as ill-proportioned. Not one beautiful nude seems irrefutably idealized, not even those in the classical antiquity. Seems like almost all the famous nudes have stirred up controversies and questions of their beauty. It took me painstakingly to glean for sartorial ensembles that match the complementary effect of black and forest green, since dark colours are best avoided for spring fashion. Differing from the other Impressionists’ penchant for using light colours, there is always a dark tonality lurks beneath Manet’s work. This painting seems almost anachronistic to juxtapose a nude with two well-dressed gentlemen. Here Manet reintroduced something known rather as an oblivious fact, that pictures can be staged.

Berthe Morisot, Child Among Staked Roses (1881)

(from left to right: Alexander McQueen, Giorgio Armani, Herve Leger. Spring 2012 via Elle.com)

In style and technique Morisot bore not a slight resemblance to her brother-in-law, Edouard Manet. The painter dexterously captured the refraction of light when it touched the flowers, and myriad rays of light created a diaphanous effect. Such otherworldly treatment of light is hardly an anomaly on other Impressionists’ canvas, one notable example can be seen in Monet’s Gare Saint-Lazare’s series.

It is not mainly nature scenes that the Impressionists were renowned for depicting, but also the flaneur scenes- the cafés, the brothels, the theatres, the circus, the everyday. Viewing the Impressionists’ paintings gives the manifestation of pleasure-seeing. It is not to negate any the pathos or disturbance underlying those joyful fusion of colours and cursory brushstrokes, but that Impressionism invites the viewers to review all the pure and the simplicity of aesthetic elements.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, On the Terrace (1881)

(from left to right: Betsey Johnson, Anna Sui, Doo-Ri, Spring 2012 via Elle.com)

Renoir stimulated my earliest admiration for art. The artist’s portrayal of wide-eyed ingénue constructed my childhood notion of what an idealized beauty should be. I only realized then as I grew older that such beauty remained illusory. The felicity Renoir’s paintings exudes, however, hardly diminishes even when situating in a world where everything is encouraged to be judged rationally and pragmatically. The exuberance of colours plays a key role in many of Renoir’s famous work. The subtle inflection of tone reminds me of what a typical Romantic music piece will be- the layers of build-up toward a dramatic climax. The climax of Renoir’s painting is its overall presentation, with the pervasive opaqueness created by the Impressionistic loose brushstrokes.

Mary Cassatt, Nurse Reading to a Little Girl (1895)

(from left to right: Carolina Herrera, Lanvin, Oscar de la Renta. Spring 2012 via Elle.com)

With the art world still squeamish to give attention to women artists in the 19th century, Mary Cassatt’s Nurse Reading to a Little Girl (1895) posed as something rather groundbreaking. The painting’s pastel-softness of green and yellow and its sketchy and wilful strokes presaged their prevalence seen in post-Impressionists like Van Gogh and Munch. However, the green and yellow in Cassatt’s painting are a staggering contrast to the unsettling derangement in Van Gogh’s, nor are the strokes indicative of an inferno burning menacingly in most of Munch’s. In Cassatt’s painting, the serenity and harmony will finally prevail.

Camille Pissarro, The Woods at Marly (1871)

(from left to right: L'Wren Scott, Alexander McQueen, Anna Sui. Spring 2012 via Elle.com)

Pissarro’s later work heralds Pointillism, initiated most notably by Seurat and Signac. Being recognized as a landscape painter, it must be a frustration for the work to be classed as something quotidian. Pissarro’s landscape is never quotidian. Amid numerous colourful dots is a passage visibly extending to an unseen end; the depth is thus created. It was an intent for the Pointillists to create an optical illusion by atomizing the painting into dots (at least that was my surmise when I was young, that the artists dissected the painting instead of painstakingly spotting on the colours), such technique does not render the painting into two-dimensional, however, it almost seems like those little dots are endowed with substance.

Edouard Manet, Luncheon on the Grass(1863)

(from left to right: Burberry Prorsum, Paul Smith, Yves Saint Laurent. Spring 2012 via Elle.com)

Manet’s nudes are my favourite, despite their bodies were once criticized as ill-proportioned. Not one beautiful nude seems irrefutably idealized, not even those in the classical antiquity. Seems like almost all the famous nudes have stirred up controversies and questions of their beauty. It took me painstakingly to glean for sartorial ensembles that match the complementary effect of black and forest green, since dark colours are best avoided for spring fashion. Differing from the other Impressionists’ penchant for using light colours, there is always a dark tonality lurks beneath Manet’s work. This painting seems almost anachronistic to juxtapose a nude with two well-dressed gentlemen. Here Manet reintroduced something known rather as an oblivious fact, that pictures can be staged.

Berthe Morisot, Child Among Staked Roses (1881)

(from left to right: Alexander McQueen, Giorgio Armani, Herve Leger. Spring 2012 via Elle.com)

In style and technique Morisot bore not a slight resemblance to her brother-in-law, Edouard Manet. The painter dexterously captured the refraction of light when it touched the flowers, and myriad rays of light created a diaphanous effect. Such otherworldly treatment of light is hardly an anomaly on other Impressionists’ canvas, one notable example can be seen in Monet’s Gare Saint-Lazare’s series.

It is not mainly nature scenes that the Impressionists were renowned for depicting, but also the flaneur scenes- the cafés, the brothels, the theatres, the circus, the everyday. Viewing the Impressionists’ paintings gives the manifestation of pleasure-seeing. It is not to negate any the pathos or disturbance underlying those joyful fusion of colours and cursory brushstrokes, but that Impressionism invites the viewers to review all the pure and the simplicity of aesthetic elements.

Comments

Post a Comment